Reading Time: 9 minutes

The topic of this blog post is one I only started to explore myself in the past year or so. I was shocked, at first, when it sunk in how ableist diet culture is, with healthism and anti-fatness/sizeism as the links. I realized how ablest (and healthist) my own thinking was back when I was deeply enmeshed in diet culture, myself. And now that I see this darker side of diet culture, I can’t unsee it, and I want you to see it, too.

Diet culture is just one of many social systems in which people are treated inequitably. It often overlaps not just with ableism, sizeism and healthism, but also with racism, sexism, ageism and classism.

Diet culture supports interpretations of personal health choices as moral character — it’s not just about weight loss. Diet culture does not support the value of all bodies, and diet culture does not exist in a vacuum.

Even if you don’t consider yourself to be on a “diet,” because you live within diet culture, you will still have thoughts, beliefs and behaviors — conscious or unconscious — that have been strongly influenced by diet culture. Unless you do the work to free yourself, of course.

Closely related to diet culture is fitness culture, which, not surprisingly, is also healthist and ableist, sending subtle or not-so-subtle messages that exercise should be used to “overcome” or avoid disability, because disabled bodies have less value.

What is “disability”? What is “ableism”?

So, what do I mean when I say “disabled”? I’m not only talking about needing to use a wheelchair, a walker, a cane or other mobility assistance devices. Disabilities can be visible, or not visible. Someone with a health condition that affects their strength, endurance or mobility would be disabled, and that may not be entirely visible. Or, someone could be neurodivergent, which often is invisible.

“Neurodivergent” is term for people with cognitive and/or neurological processes that differ from what is considered — by cultural/societal and medical standards — to be “typical” or “normal.” This includes people with autism, ADHD, anxiety, depression and borderline personality, as well as people who are highly sensitive to sensory stimulation.

I found this definition by lawyer and social justice activist Talila “TL” Lewis to be detailed and powerful:

“A system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in eugenics, anti-Blackness, misogyny, colonialism, imperialism and capitalism.

“This systemic oppression leads to people and society determining people’s value based on their culture, age, language, appearance, religion, birth or living place, “health/wellness,” and/or their ability to satisfactorily re/produce, “excel” and ‘behave.’

“You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism.”

What ablism and anti-fatness/sizeism have in common is the ideal — held by the medical system and society at large — that being fat and being disabled are both abnormalities that the individual should work hard to overcome. Also, that having a body that is abnormal in this way means that you are not normal, and not quite human. [Note that I use the word “fat” as a neutral descriptor, like short or tall.]

Which is complete and utter bullsh*t.

A first look at ableism and anti-fat bias

Just as you don’t have to be disabled to experience ableism, you don’t have to be fat to experience anti-fat bias. If you are a thin person who diets or exercises to remain thin, it’s at least in part because you are afraid of becoming fat. It may also because you are afraid of becoming “unhealthy” or experiencing a loss of mobility.

I’ve had clients in larger bodies who also happen to have some mobility issues tell me how important it was for them to try to walk or move “normally.” This is less about how movement feels in their body, and more about how they might be judged by other if they are fat AND they walk slowly. I’ve also had neurodivergent clients in larger bodies feel increased pressure to mask signs of their neurodivergence.

Systemic oppression based on whether someone adheres to societal ideals of “normalcy” and “intelligence” impacts disabled and neurodivergent people, as well as fat people. This can include:

- Focusing on reducing “symptoms” of neurodivergence — or on losing weight — through nutrition interventions.

- Seeing neurodivergence — or “excess” body fat — as something to “cure.”

- Focusing only on how neurodivergent and fat individuals can cope in an ableist/anti-fat world instead of focusing on making the world more accessible and friendly to a diverse range of people.

On that last point, people living in fat bodies may have trouble finding appealing clothes (or any clothes that are not custom-made) that fit. They may dread going to restaurants, theaters or on airplanes because they know (or aren’t sure) if the chairs or seat will accommodate their bodies. People living with a physical disability may also have trouble finding clothes and seats (or entire buildings) that are designed to meet their needs.

How healthism plays a connecting role

Healthism is a philosophy that overemphasizes individual responsibility in health outcomes and prioritizes pursuing health above all else. This can include:

- Demonizing eating for pleasure, joy, comfort, or stimulation. (There should be no shame in finding pleasure/joy/comfort from food, and food can be an important form of stimulation, or stimming, for some neurodivergent folks.)

- Shaming people for choosing convenience foods, despite the fact these foods may be enjoyable, and may be a saving grace for busy people as well as people who find it challenging mentally or physically to cook a meal “from scratch.”

- Seeing health (and the pursuit of health) as a moral obligation.

I have a lot to say on that last point, but let’s start by pointing out what might be obvious: Many people are (reluctantly) willing to give fat people a pass “as long as they’re healthy.” This is part of the “good fatty” trope — be active, attractive and productive, and don’t accept your current body as OK. (If you’re fat and dare to like yourself, someone may accuse you of “glorifying obesity.”

I’ve had many clients in larger bodies tell me they feel they need to look like they’re trying to lose weight or “get healthy” — ordering the salad, going to the gym, bragging about their excellent cholesterol and blood sugar levels — even when they are in the process of unsubscribing from diet culture and making peace with food and their bodies.

When someone “concern trolls” a fat person on social media (or elsewhere), what do they say? Usually something like, “but you’re not healthy” or “you’re going to get diabetes.” Yep, ableism (and healthism) are inherently baked into anti-fatness.

While it’s true that weight and health are not closely linked (association does not prove causation), I’ve come to follow statements I make about that point with another statement that can be even mind-blowing: being healthy and/or pursuing health is not a moral imperative.

Mic drop.

Health isn’t a guarantee, or a measure of worthiness

Quite simply, “health,” as it is typically defined, is not a resource that is available to everyone. Some people never have that resource. Other people intermittently have it. Still other people have it for a while, then don’t have it, and never have it again.

Like it or not, if we are lucky enough to live long enough, things are going to happen to our bodies. We might find that our joints ache, that we gain weight, that our blood pressure trends higher, that we need to use a walker or a wheelchair, that we get cancer. Our bodies are no less worthy. We are no less worthy.

When I was still doing “non-diet weight management” (which I eventually realized was not a thing) I would often help clients set “meaningful” goals. In other words, instead of using fitting into “skinny jeans” as a goal, we would use “keeping up with your kids” as a goal. Yep, that’s totally ableist. Some parents will never be able to “keep up with” their kids or get down on the floor to play with their kids. That doesn’t make them bad or ineffective parents.

Fat people and neurodivergent people have always existed, so alarmist headlines (and the public health machinations behind them) about the “ob*sity epidemic” or the “autism epidemic” really spread the idea that anyone who diverges from what has been labeled “normal” should be eliminated or erased. We saw this clearly in one not-so-charming chapter of our country’s history involved what were known as “ugly laws.”

From 1867 to the beginning of World War I, some U.S. cities enacted so-called “ugly laws” banning people deemed “diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object or improper person” from public spaces. While these laws became less enforced over time, Chicago didn’t repeal its “ugly law” until 1974, when an alderman took up the cause, calling the law “cruel and insensitive” and “a throwback to the Middle Ages.”

A second look at ableism and anti-fatness

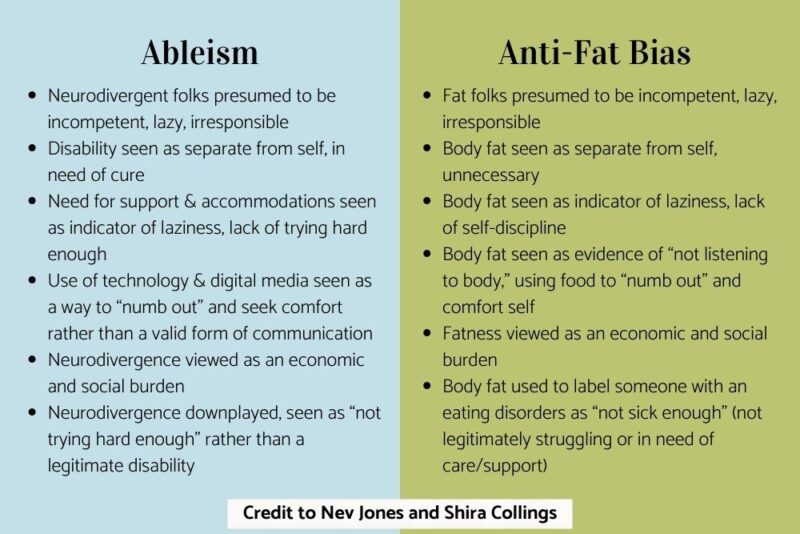

For this section, and the graphic above, I give heavy credit to mental health researcher and professor Nev Jones and therapist Shira Collings, who gave a talk together at an RDs for Neurodiversity conference I attended earlier this year.

They said the concept of “excess” is an underlying thread beneath anti-fat bias and ableism. Body fat/fatness is seen as excess body tissue, and as a result of excessive eating. The message is also that the body itself is almost “excess” – that body size is independent of who we are. Same with neurodiversity – disability and disability accommodations as an “excess,” accommodations as unnecessary.

Both fat and neurodivergent people face objectification and disempowerment, as they are not seen as the experts on their own needs. I think this is true for people who have other forms of disability, as well.

Jones and Collings pointed out that neither body fat or neurodivergence are things that need to be cured or eliminated, and that our bodies are parts of our minds and ourselves.

- Our cognition (thinking) is influenced by our bodies, and weight suppression can have a significant negative impact on our thinking.

- When someone is within their set point range—which may involve being fat—this is necessary and in fact crucial to how they function and who they are.

There’s some serious food for thought there.

So now what? Ways to reflect

Did this post feel like a lot? If it did, that’s OK. I hope it opens a door to exploring your own thoughts, feelings, beliefs and assumptions about what bodies (and minds) are worthy and valuable. Here are some questions to get you thinking:

- What ways of being different get labeled as “bad” or “inferior” in our society? Do you agree or disagree with these labels?

- In what ways do you label other people as being less worthy? Do you feel like you do this consciously, or unconsciously (like maybe you absorbed these ideas from society but haven’t really examined or questioned them)? How are these people different from you? Do you notice any fear that you might someday be like these people?

- Should people have to change their bodies or minds to “fit in,” or should our society and its systems evolve to be more inclusive of all kinds of people?

- Do you judge (consciously or unconsciously) people who are “unhealthy”? Do you make a distinction between having a disease or disability that is “preventable” vs. one that’s not? Why?

- Do you believe it’s a moral imperative to pursue health? Why or why not? If you do, how does this align (or conflict) with other beliefs you have about body autonomy?

- Do you believe that we have personal control over our health? If yes, can you think of any or examples where that’s not the case?

- If you know that you judge people based on their size, ability, health or other factors, how does that make you feel? Have you been judged by others (or yourself) based on something about you that’s different? How did that make you feel?

- Do you stand opposed to some forms of oppression (say, racism) but find that you let other forms of oppression slide by? Why?

Some of these questions might reveal answers about yourself that make you cringe. If so, that’s OK. Approach them with curiosity and self-compassion, and if you discover that you have some beliefs or mindsets that need to change, then start to change them. If we aren’t aware of our thoughts, feelings, beliefs and behaviors, then we stay stuck. Awareness (again, paired with curiosity and self-compassion) opens the door to knowing better, and doing better.

Carrie Dennett, MPH, RDN, is a Pacific Northwest-based registered dietitian nutritionist, freelance writer, intuitive eating counselor, author, and speaker. Her superpowers include busting nutrition myths and empowering women to feel better in their bodies and make food choices that support pleasure, nutrition and health. This post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute individualized nutrition or medical advice.

Print This PostOriginal Article

Print This PostOriginal Article